Volume of a Sphere

Yesterday (as I type this)

Fermat's Library

on Twitter tweeted this:

|

|

|

It was only 282 years ago that Euler presented

in his textbooks the exact formula for the volume

of a sphere.

|

|

|

Click here to see the original

Then there was an image with the actual formula: $V=\frac{4}{3}{\pi}r^3$.

Over 12 thousand people "Liked" the tweet, but someone said:

- ... how would you go about proving this one?

So here is how we can prove it.

Volume of a cone

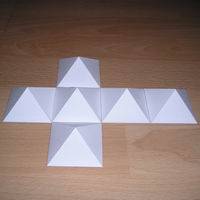

Firstly, think about a cube. We can think of the cube as six pyramids

put together with their apexes meeting in the middle. The apex of each

pyramid is in the exact centre of the cube, so if the cube has a side

length of 1, then the pyramids will have to have "height" $\frac{1}{2}$.

Then because there are six identical pyramids we can conclude that each

pyramid is one sixth of the volume of the cube.

- So a square-based pyramid of side length 1 and height $\frac{1}{2}$ has a volume of $\frac{1}{6}$.

Imagine doubling the height of the pyramid. That would double the volume,

so now the volume is $\frac{1}{3}$.

- So a square-based pyramid of side length 1 and height 1 has a volume of $\frac{1}{3}$.

|

A few people have asked about this. Imagine taking your pyramid,

or indeed, and shape, and think of an approximation made up of tiny cubes.

Now double each cube in height. Doing so doubles the volume of each

little cube, and therefore doubles the volume of the whole thing. But

it also doubles its height.

Generalising this argument, we can see that scaling by some factor in

one direction increases the volume by that factor.

You may need to think about that for a bit ... |

Thinking about scaling this vertically:

- If we multiply the height by 5, the volume is now $\frac{5}{3}$;

- If we multiply the height by 8, the volume is now $\frac{8}{3}$;

- If we multiply the height by $h$, the volume is now $\frac{h}{3}$,

- which can also be written as $\frac{1}{3}h$.

Now think about scaling the base. If we make the edges of the base

twice the size, the area of the base is four times the size, and the

volume similarly increases by a factor of 4. Thinking carefully about

this we get the following:

- If the area of the base of a pyramid is $A$,

- and the height is $h$,

- then the volume is $\frac{1}{3}Ah$.

This isn't limited to square-based pyramids, though, it's true of every

pyramid and every cone. Take any shape of area $A$ in the plane, and any

point above it. Join that point to every point on the rim of the shape

to make a cone-like "thing", and the volume of that resulting "thing" is

$\frac{1}{3}Ah$.

Comparing volumes

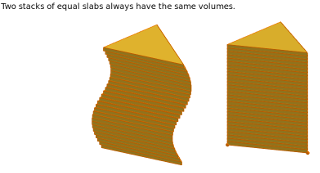

Consider two identical stacks of coins. The volumes of the stacks are

the same, and this remains true even if you slide some of the coins

sideways to make one of the stacks "wonky".

Using that as our inspiration we introduce "Cavalieri's principle"

which says this:

- Given two things standing on a table, if every slice

taken parallel to the table results in cross-sections

of the same area, then the two things have the same

volume.

Basically, if you have two stacks of things, and at every height the

areas are the same in each, then the volumes are the same. You can

play with an interactive version of the idea here:

So in some cases we can compare volumes as follows:

- Put the two items on a table;

- Take a slice at some height;

- Measure the resulting area of each cross-section;

- If they are always the same,

- the two items have the same volume.

(And yes, that was literally a re-statement of Cavalieri's Principle.)

The Cone, the (Hemi)-Sphere, and the Cylinder

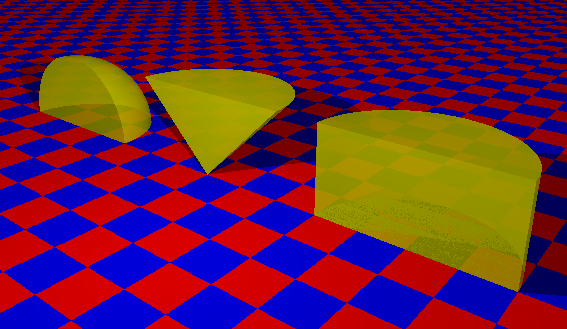

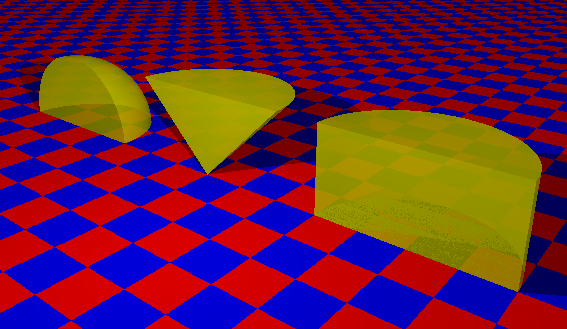

Perspective view

|

Now pick some value, $R$, which we are going to use as a radius for

a cone, and hemisphere, and a cylinder. We take a hemisphere, cone,

and cylinder, and arrange them in a line, with the cone "inverted".

This image here has them sliced vertically to show a cross-section,

as that's how we will be thinking about them

So let's have a look at that cross-section.

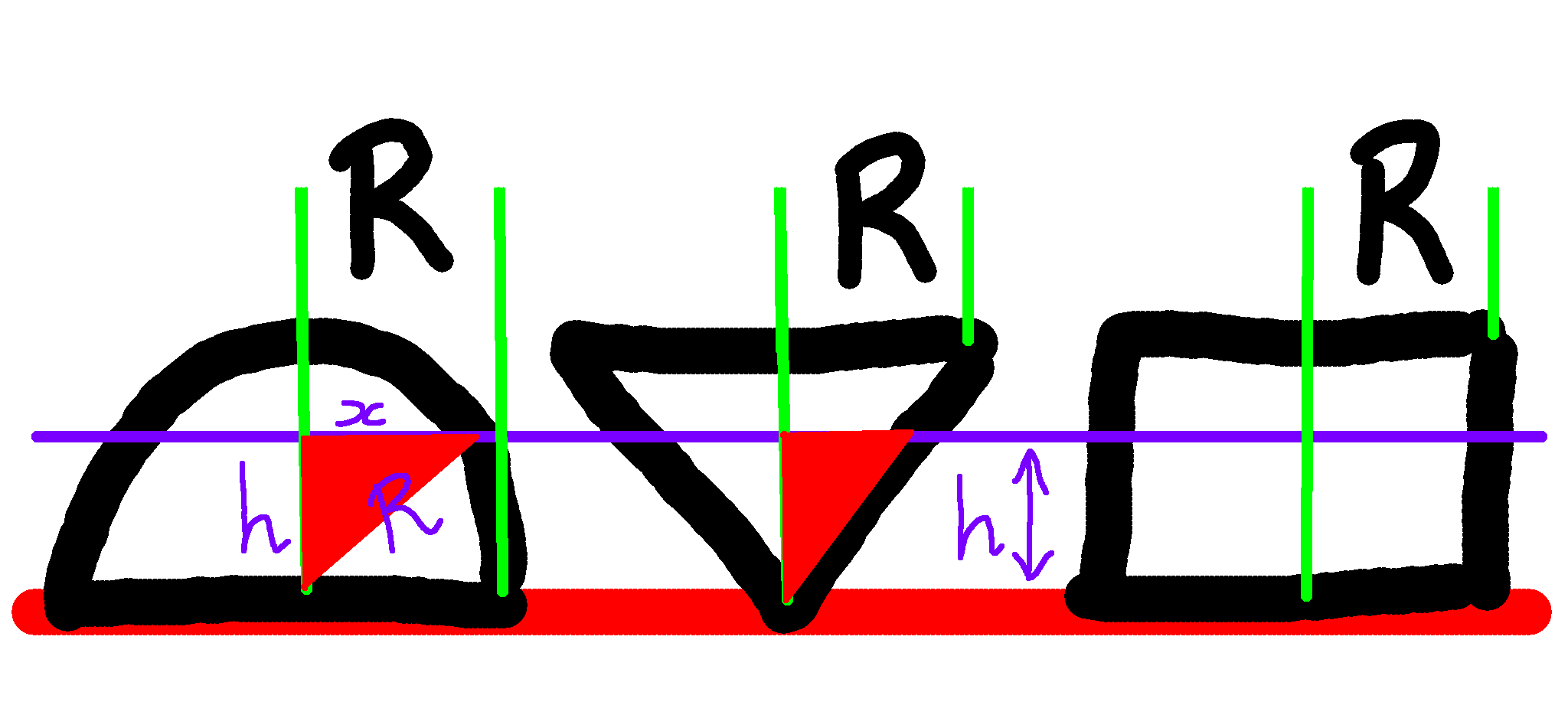

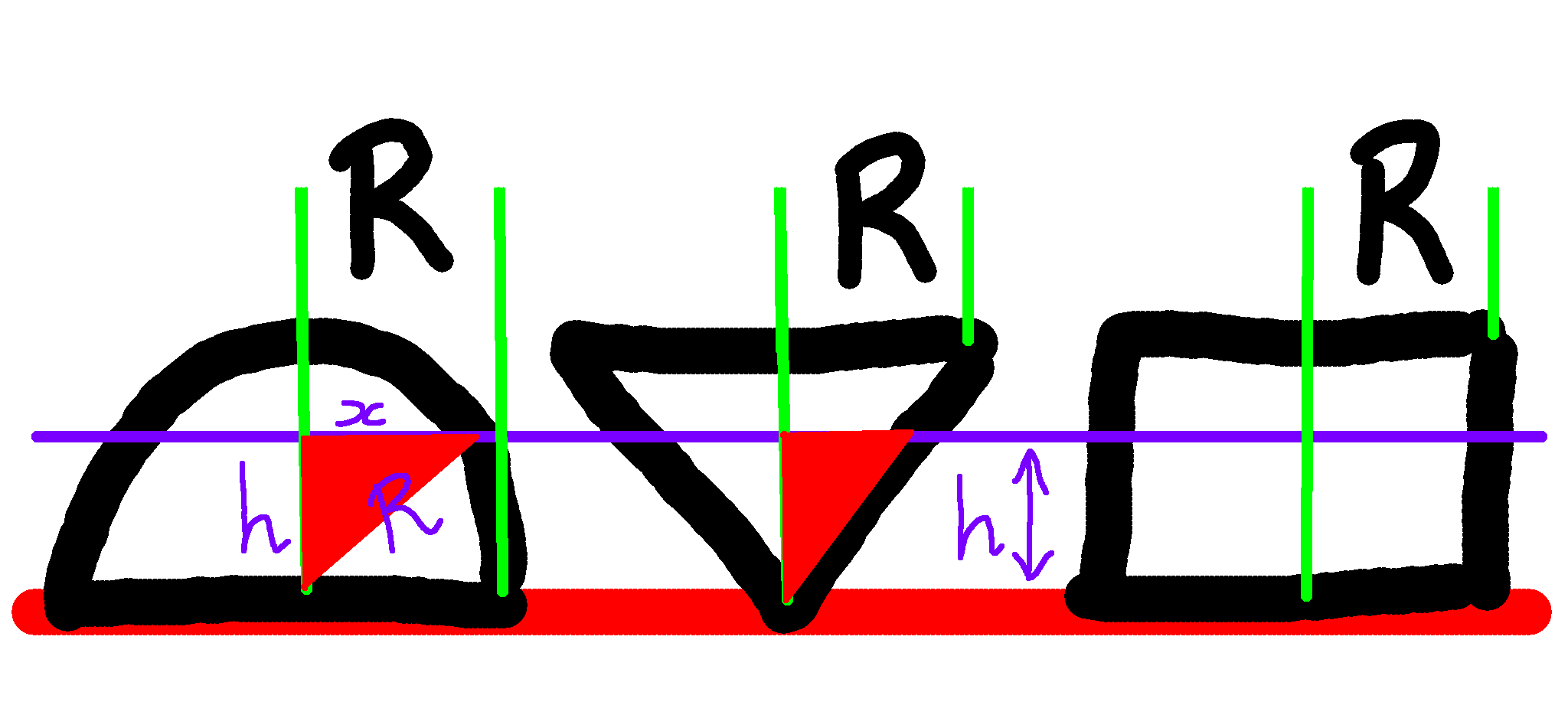

Taking a "side on" view here, seeing the hemisphere, inverted cone,

and cylinder, all from the side, and we have taken a slice through

them all at some arbitrary height $h$. The three objects here are

all of height $R$ and radius $R$, so the sides of the cone are at

45 degrees to the table on which they rest (even though in my rough,

hand-drawn diagram they don't look like it).

Hemi-sphere, Cone, and Cylinder

|

We know that taking a slice through the cylinder will result in a

circle of radius $R$, and hence area ${\pi}R^2$. The slice through

the cone will also give a circle, and when we realise that the red

triangle is (despite the drawing!) a 45-45-90 triangle, we can see

that the radius of the circle will equal the height of the slice,

and so the radius of the slice in the cone will be $h$, the height

of the slice. So its area will be ${\pi}h^2$.

In the case of the slice through the hemisphere, that will also be a

circle, and we can compute its radius (and hence area) by using our

old friend, Pythagoras' Theorem. We have a right-angled triangle

with hypotenuse the radius of the hemisphere, hence $R$. The height,

and hence one short side, is $h$, so we have the equation:

Rearranging that we have $x^2=R^2-h^2$ and so the area of the slice

section is ${\pi}(R^2-h^2)$.

Combining the results

Now for the pay-off. Looking at the slices through the hemisphere

and cone, their total area is:

- ${\pi}(R^2-h^2)\;+\;{\pi}h^2$

But that simplifies to be ${\pi}R^2$, which is the area of the slice

of the cylinder.

So using Cavalieri's Principle;

- the volume of the hemisphere

- plus the volume of the cone

- equals the volume of the cylinder.

|

The cylinder has volume ${\pi}R^3$, because that is the height times

the area of the base. The cone has volume $\frac{1}{3}{\pi}R^3$,

being one third of the base area times the height. So the volume of

the hemisphere is the difference, which is $\frac{2}{3}{\pi}R^3$.

Therefore the volume of the full sphere is twice that.

Thus the volume of a sphere of radius $R$ is $\frac{4}{3}{\pi}R^3$.

Further reading ...

A previous blog post gave a different derivation of this result:

Related is this page:

There are more pages on these results that you can find by searching

for Cavalieri's Principle, Archimedes, and more.

If there's anything on this page that you think is unclear or needs

expanding, please let me know and I'd be happy to revisit anything

that I think should be enhanced or updated.

Good luck!

Send us a comment ...

|

Suggest a change ( <--

What does this mean?) /

Send me email

Suggest a change ( <--

What does this mean?) /

Send me email